Sir William Armstrong

A Proto-Technocrat of the new British Imperial Military-Industrial Complex

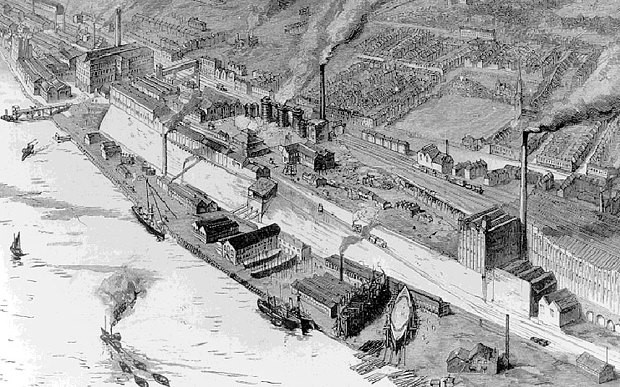

At the young age of 25 years old, William Armstrong (1810–1900) had his first of many innovative ideas that significantly advanced technological change. While fishing on the banks of the River Dee in Dentdale, North Yorkshire, he watched a nearby water wheel, and noticed that so little of the water power was being captured by the wheel. Following the rejection of his idea of a rotary engine powered by water, he then devised a piston engine that he envisaged could drive. The idea behind Armstrong’s steam-powered hydraulic crane was that it would be able to unload ships faster and more cheaply than existing cranes. The blueprint for this invention was published in a late-1838 edition of Mechanics Magazine and, the following year, he had a prototype in place for trials. In 1842, the first of Armstrong’s hydraulic cranes were being employed on the quayside of the River Tyne. Two years later, in 1847, Armstrong entered a partnership with four Newcastle businessmen to establish a factory in over five acres of land at Elswick, two miles west of the centre of Newcastle, and on the north bank of the Tyne. So began the life of the famous Elswick Works, which became Newcastle’s largest Victorian employer, and a major supplier of guns and ammunition for the British government, as well as many other countries all over the world.

During the years 1847–63, Elswick works produced approximately 2000 hydraulic cranes, as well as locomotives, steam engines, boilers, caissons, dock gates, bridges and pontoons, dams, barges and wrought iron dredgers. Yet it was November 1854 that William Armstrong turned his attention to weaponry. Upon learning of the difficulties encountered by the British troops in moving two heavy muzzle-loading guns to the top of a hill during the November 1854 Battle of Inkerman, Armstrong designed the concept of lighter type of field gun that had a rifled barrel made from wrought iron, that could fire shells (instead of balls) loaded into an opening at the back of the gun. When the Secretary of State for war, the Duke of Newcastle, became aware of these breech-loading guns, he requested several of the guns to be constructed for the government on ‘an experimental basis’. A five-pounder gun was successfully tested in 1855, followed by an 18-pounder in 1856. Experts were greatly impressed’ with the accuracy and range of Armstrong’s new gun. This melding of politics and scientific engineering applied to weaponry was not before time, for in the 1851 Great Exhibition, Alfred Krupp of Essen proudly demonstrated his new six-pounder gun made of cast steel – a new continental rival was showing its technological prowess in the heart of the British Empire.

In a remarkable gesture of patriotism, Armstrong signed all patents to his breech-loading rifled gun design over to the British government, for which he was awarded a knighthood by Queen Victoria on 23 February 1859. Armstrong was then offered the post of Engineer of Rifled Ordnance to the War Department, and became the Chief Superintendent of Woolwich Arsenal. To avoid criticisms of a conflict of interest (being a senior government official and owner of the company in receipt of government contracts), a new business venture called Elswick Ordnance Company was established in which Armstrong had no role. Yet the government contracts to supply the guns were expired within only three years, for a campaign against Armstrong’s breech-loading guns – driven by conservative traditionalists within the army and spear-headed by the leading rival armaments companies (most notably Joseph Whitworth’s of Manchester). This did however give Armstrong the opportunity to merge the two Elswick companies to form Sir W.G. Armstrong and Company in 1864. This company was later merged with the Tyneside Charles Mitchell shipbuilding company to form Armstrong, Mitchell and Co. which went on to supply nations warships for nations across the globe, including (somewhat ironically) Austria-Hungary, Turkey, Italy, and Japan. Of equal importance, severance from the British government allowed Armstrong to sell breech-loading guns to any interested parties. By 1863, the Armstrong gun had been trailed by leading rivals to the British Empire, including Russia, Turkey, Austria, and the USA – the latter of which became a lucrative market for the Armstrong company and both Unionist and Confederate states purchased Armstrong guns for the American Civil War.

A major project of the Armstrong Works at Elswick was the manufacturing and installation of the great Swing Bridge linking Newcastle to Gateshead by road across the River Tyne. This bridge first swung open on 17 July 1876 to permit the passage up the Tyne for the Italian cargo ship, Europa, to collect from the Elswick Works the first of six new 100-ton guns that had been purpose-built for the Italian Navy. More strategically, this bridge created the ‘gateway to the sea’ that enabled the Elswick Works to expand its markets internationally. Armstrong’s also produced the machinery that opens and closes the Tower Bridge across the River Thames.

By 1900, the Elswick Works employed many thousands of people, producing guns of all sizes – from machine guns to 100-ton Dreadnought-style breech-loading ordnance – for many international customers. As Ken Smith noted in his excellent introductory booklet which refers to Armstrong as the Emperor of Industry, Armstrong’s Elswick Works ‘went on to make an immense contribution to Britain’s efforts during the First World War’, in which it ‘manufactured 13,000 guns, over 14 million shells, and around 100 tanks’. Quite a number of the warships that fought the Battle of Jutland were also manufactured at Elswick. Armstrong’s also expanded into aircraft production with its bi-plane factory on the outskirts of Newcastle.

With the war looming, they created the ‘Arial Department’ in 1913 at Dukes Moor, Gosforth where they set about producing 250 R.A.F. (Royal Aircraft Factory) BE.2c’s as part of a governement order. The Government then asked them to recruit Dutch Engineer Frederick Koolhoven (who had formerly been Chief Designer at British Deperdussin) and his first airraft was the F.K 1 which flew in September 1914. Despite a promising start the F.K 1 was never produced. Virtually all of AW’s productions during the war were ‘F.K’ designs, by far the most successful of which was the F.K 8 ‘Big Ack’ and some 1,650 examples were produced at Gosforth. There is a direct genealogy that connects Armstrong’s company to today’s BAE (see www.baesystems.com for more).

After the First World War, Armstrong’s merged with the famous Vickers armaments company of Sheffield and Barrow to form Vickers-Armstrong Ltd., which manufactured a significant number of guns and tanks for the Allies during the Second World War. This firm’s Walker Naval Yard in the east end of Newcastle (which replaced the Elswick Works shipyard) also launched and repaired man Allied warships during the Second World War.

As the demand for industrial weaponry declined after the Second World War, so slowly the traces of the great Armstrong companies faded into history. The Elswick Works – for so long the recognisable feature of the Newcastle Quayside was demolished in the mid-1980s. A new business park was constructed in what is now known as ‘Armstrong Way’.

By the 1870s, breech-loading ordnance was firmly accepted in continental armies and navies yet, from 1864, the British services had reverted to muzzle-loaded guns. Advancements in propellants was the spur to reinvigorate interest in breech-loading guns in British service. Research by chemists Andrew Noble and Frederick Abel of Woolwich led to slower burning powders that had less sudden impact on the gun barrels, and also added velocity to the projectiles. This naturally led to longer, slimmer barrels (the squat, bottle-shaped barrels of earlier guns were designed to cope with the sudden burst of energy from the old black gunpowder). The reversion to breech-loading was therefore an obvious evolution.

Elswick Works, Circa 1895

Elswick Works, Circa 1895

Armstrong’s home became a focal point for leading politicians and scientists. Among the politicians were Joe Chamberlain and First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord George Hamilton, who both visited Cragside in 1889; among the scientists were Thomas Huxley. Part of the attraction was his unique and unprecedented application of hydro-powered electricity to his Cragside home, for which he had requested the scientific input of the German inventor Carl Siemens, and of Joseph Swan (inventor of the incandescent lamp that later evolved into the light bulb). It was Armstrong’s foray into electrical experimentation that led to his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

The Newcastle newspaper, Daily Chronicle commented in 1896 that through ‘the din of countless hammers may be heard the songs of happy children and the rejoicing of parents to whom Lord Armstrong’s scientific wizardry has supplied the means of material well-being’.

The mid-nineteenth century application of technologies and industrial finance to the development and refinement of weapons was accompanied by the emergence of a prototype of the military-industrial complex that became so prominent a focus of discussion and controversy a century later. Sometimes the various connections of these early complexes were purposely forged; sometimes they emerged quite innocently because of personal contacts ripening into friendships. Whatever their particular nature, Armstrong and his new country home of Cragside played an important part in the process (p. 212).

References

David Dougan, The Great Gun-maker: The Life of Lord Armstrong (London: Frank Graham, 1970).

Ken Smith, Emperor of Industry: Lord Armstrong of Cragside (Newcastle: Tyne Bridge Publishing, 2000).

Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher:

Naval Technocrat Extraordinaire

The greatest irony of the First World War was that the mightiest instruments of warfare were used with the greatest caution. The British and German Dreadnoughts rendered all earlier battleships obsolete, yet paradoxically proved to be the last generation of traditional ‘big-gun’ battleships. In June 1911, Fisher wrote that the Royal Navy ‘could take on all the navies in the world’: ‘Let ‘em all come!’ he declared with bombastic confidence. With pugnacious statements like this, it is plain to see why so much was expected of these enormous capital ships. The British imagined nothing less than the British Admiral of the Fleet Lord Jellicoe becoming a ‘twentieth century Nelson’; they wanted a new Trafalgar, and expected it. Lord Nelson had once written that there was ‘no better negotiator in the councils of Europe than a fleet of English line-of-battleships’, and for this primary purpose the British Dreadnoughts were built. In the words of the great naval historian, Arthur Marder, Britain was ‘hypnotized by the past’, as she was wedded to the eighteenth-century idea that the essence of naval warfare was two opposing fleets of capital ships battering each other to death.

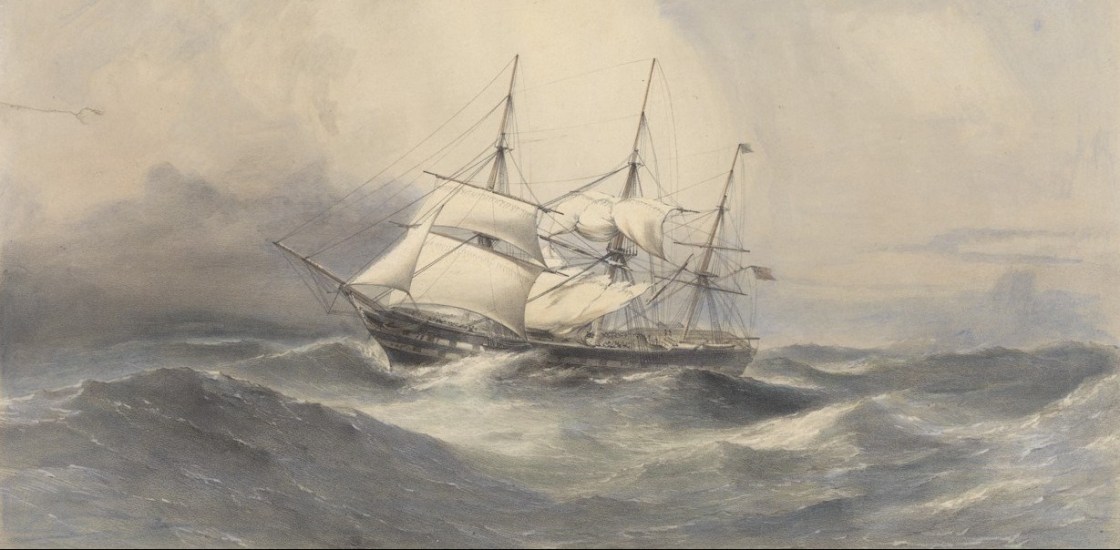

The 84-guns Ship-of-the-Line HMS Calcutta, full sail in 1858 (Source: Wikicommons)

The 84-guns Ship-of-the-Line HMS Calcutta, full sail in 1858 (Source: Wikicommons)

The man primarily responsible for shaking the Royal Navy out of her Nelsonic stupor was John Arbuthnot Fisher, First Sea Lord from 1906 to 1910. Fisher joined the Royal Navy at the age of thirteen years old in July 1854, just as the British Government was deciding to engage the Russian Empire in the Crimean Peninsula. He therefore enlisted at a time when the Royal Navy was still the Glorious Navy of Nelson: indeed, the young Fisher was first ‘learnt the ropes’ aboard Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory in the naval dockyards at Portsmouth, before being assigned to HMS Calcutta, an 84-gun wooden ship-of-the-line. Fisher was therefore an impressionable young naval recruit at a fascinating period of change, in which the Industrial Revolution was forcing the British Admiralty to consider technological advancement, and rethink hundreds of years of traditional naval orthodoxy. Hybrid ships combining sail and steam had been crossing the Atlantic some thirty years before Fisher joined the Calcutta, yet the blue-water aristocracy that dominated the admiralty clung doggedly to the belief (or excuse) that steam engines were unreliable and not for the Royal Navy and its deeply-rooted traditions that had served the nation for hundreds of years. Such fatalistic conservativism also resisted steel ships on the grounds that wood floated, and iron sank. The last of the wooden frigates was decommissioned in 1861, and the first armoured battleship, HMS Warrior, was launched two years later, to which Fisher was assigned for gunnery duties.

HMS Warrior escorting the royal yacht, March 1863, by S. Francis Smitheman

HMS Warrior escorting the royal yacht, March 1863, by S. Francis Smitheman

In 1862, Fisher was assigned to HMS Excellent, an old three-deck ship-of-the-line moored in Portsmouth harbour and used as a gunnery training school. At this time, Excellent was evaluating the performance of the Armstrong breech-loading guns and comparing it against the traditional Whitworth muzzle-loading guns. In March 1863, Fisher was appointed Gunnery Lieutenant aboard HMS Warrior, the first all-iron seagoing armoured battleship and the most powerful ship in the fleet. Built in 1859, she marked the beginning of the end of the Age of Sail, and was armed with both Armstrong breech-loading and Whitworth muzzle-loading guns.

HMS Excellent, Calcutta and Vernon, circa 1872, the Royal Navy’s floating Gunnery School. Source: http://www.mcdoa.org.uk

HMS Excellent, Calcutta and Vernon, circa 1872, the Royal Navy’s floating Gunnery School. Source: http://www.mcdoa.org.uk

The following year, Fisher returned to Excellent as a gunnery instructor, where he remained until 1869. Towards the end of his posting he became interested in torpedoes, which were invented in the 1860s, and he championed their cause as a relatively simple but effective weapon capable of sinking battleships. Fisher was fascinated by technology and saw that new innovation in weapons, ship design and aviation would transform the nature of naval warfare. He also believed that the Royal Navy had to be at the forefront of this technological leap forward. His third and final appointment to Excellent was in 1872, during which he lectured on, and negotiated the purchase of, the Royal Navy’s first Whitehead torpedoes. As Superintendent of HMS Excellent, Jackie Fisher also supervised the construction of the latest warships and, as Third Sea Lord, he was responsible for the construction of the first torpedo boat destroyers of the Royal Navy from the late-1890s. (ever since named ‘destroyers’ after Fisher’s suggestion). After a spell as Commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, Fisher was made Second Sea Lord in 1902 – a role in which he reformed officer training.

One biographer wrote that Fisher ‘captured and held the popular imagination as no British sailor had done except Nelson’. The primary reason for this fond memory of ‘Jackie’ Fisher is that he radically altered the traditional ‘Navy of Nelson’ to one that was ready to fight the First World War. While at the Admiralty, Fisher surrounded himself with like-minded officers with technical prowess, and implemented necessary modernizing naval reforms with great vigour and enthusiasm. Fisher’s reforms inevitably had to be cost-effective, given the Liberal Government’s demands for social reforms. He therefore sold 90 ships and placed another 64 in reserve, believing all 154 to be ‘too weak to fight and too slow to run away’. Although this compromised the two-power standard, it was essential in modernizing the Royal Navy. Fisher then re-organised the fleet. All the latest ships (including those he designed) were stationed in Gibraltar and in the Channel with the German threat in mind. Fisher also created the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) so that Britain had a large reserve to call upon in war.

Among the greatest of honours bestowed upon Fisher was when he was appointed in 1903 Commander-in-Chief of Portsmouth naval base, with HMS Victory as his flagship. The connection between Nelson and Fisher was complete. The following year, Fisher was promoted to First Sea Lord. He believed that the way to ensure naval supremacy was with submarines – indeed, the submarine did become the primary threat to Capital Ships. Fisher believed that submarines would render the battleship obsolete – ‘what is the use of battleships as we have hitherto known them? NONE! Their one and only function – that of ultimate security of defence – is gone – lost!’, he wrote. Yet the submarine was to remain peripheral in Royal Navy strategic thinking during Fisher’s time as First Sea Lord. The primary reason for this is that his Admiralty peers were much less technologically minded, and insisted that submarines were simply ‘ungentlemanly’.

HM Submarine No 3, one of five ‘Holland’ type experimental craft, circa 1903, in front of HMS Victory (Source: Wikicommons).

HM Submarine No 3, one of five ‘Holland’ type experimental craft, circa 1903, in front of HMS Victory (Source: Wikicommons).

A document from the Cabinet Papers in the National Archives truly epitomises Fisher’s absolute belief in technological developments transforming the Royal Navy. Entitled ‘The Submarine: A Contribution to the Consideration of the Future of Sea-Fighting’, Fisher highlighted the repeated Admiralty resistance to modernizing technological development: steam engines being ‘fatal to England’s Navy’; an Admiralty Board minute vetoing iron ships as ‘iron sinks and wood floats’; Admiralty objection to breech-loading guns; ‘virulent opposition to the water boiler’; wireless being voted as ‘damnable by all the armchair sailors’, and so on. Fisher even referred to ‘flying machines’ that had not been thought possible by scientists, becoming ‘as plentiful as sparrows’. He ended this document with the prediction that the submarine was the ‘coming type of war vessel for sea fighting’. Fisher echoed this premonition during the annual review of the fleet at Spithead in 1905, where upon witnessing the first squadron of submarines in the Royal Navy, he remarked ‘there goes the battleship of the future!’. How right he was!

HMS Invincible, circa 1907 (Source: Wikicommons)

HMS Invincible, circa 1907 (Source: Wikicommons)

This belief in the future of the submarine did not deter Fisher from inspiring a building programme of battlecruisers which he helped to design. His new Lion-Class battlecruisers (his ‘Battle-cats’; often referred to as ‘Fisher’s Oddities’), were designed to sink any ship fast enough to catch them, and run from any ship capable of sinking them. They had light armour for speed, but also had powerful guns. They were no match, however, for the forthcoming Dreadnoughts. HMS Invincible (arguably, the most ironically named ship) was the first of the battlecruisers to be launched, and the first to be destroyed – for she exploded in the 1916 Battle of Jutland. Fisher also had a hand in designing the Dreadnoughts that accelerated the naval arms race with Germany.

Front and Side Views of HMS Dreadnought (Source: Wikicommons)

The German High Seas Fleet had its strategy already written – meet and defeat the British fleet. Its primary purpose for constructing Dreadnoughts was primarily to challenge British maritime supremacy. Under Admiral Tirpitz, the new and improved Germanic arm of the Kriegsmarine was at the peak of modernity, with cutting edge technological firepower manned by highly skilled technically trained sailors. Famed British historian, Richard Hough, suggested that handled aggressively and skillfully, the High Seas Fleet could have beaten the Grand Fleet in 1914 in a level fight.

The dominant figures responsible for bringing these two great fleets into the twentieth century were Fisher and Tirpitz. In their respective posts, they created environments of technical activity, innovation and radical advancement. For the Kriegsmarine, this was not too difficult a task, for Tirpitz was, in effect starting from scratch; as were German sailors who were taught by superbly trained officers, particularly in technology. For the Royal Navy however, the matter of technology was not so clear cut. In a way, the British Navy was like a cornered cat – wanting to thrust forward but not sure in which direction. What made matters worse was that there was little precedent to use to aid determination of further progress; the Anglo-Boer affair being a land question, and Crimean War witnessing little naval action. Although the latter did at least demonstrate that sail ships were worse than useless when fighting steamships, the first British warship without sails, HMS Devastation, was not built until 1873.

It is little wonder then that the British Navy was in a twilight zone; trapped in tradition whilst in awe of the compelling advance of scientific and technological development. It was there for all to see – the ‘furious rush’ of technology from the Industrial Revolution had transformed naval warfare – wood to iron, sail to steam, newer and bigger guns with more powerful shells, electricity, screw propellers, wireless telegraphy and newly-invented (and therefore limited) radio communication. There was also the increasingly alarming menace of underwater mines, and torpedoes fired from submarines. With Fisher’s arrival came turbine engines, water-tube boilers and further fuel conversion from coal to oil. Moreover, despite oil being a resource not available in Britain, Admiralty agreement for swift conversion throughout the fleet was incontrovertible.

Yet it was in gunnery that Fisher’s forté resided. According to historian Peter Kemp, Fisher was convinced that victory in naval battle was reward for the fleet which could hit hardest at the greatest range. He had already instituted long-range gunnery as early as 1899: as First Sea Lord, Fisher was able to provide the guns and floating gun-platforms necessary to perfect this new naval science. These he deemed essential owing to fear of what Hough called the ‘crippling underwater blow’ from torpedoes (fired from submarines and torpedo boats) that had necessitated increases battle ranges. The trouble was, no-one else could envisage the dramatic effect submarines would impose upon naval strategy. Fisher was a lone voice in the Admiralty on this issue, as he later complained to his old rival: ‘Dear Old Tirps….I don’t blame you for the submarine business. I’d have done the same myself, only our idiots in England wouldn’t believe it when I told ‘em’.

Herein lay the nub of the issue of any future naval confrontation. The Dreadnoughts were according to Hough the ‘most magnificent and provocative weapon of war devised by man’, and the technology harnessed to make them so, was ‘cutting-edge’. Yet such awesome might was wasted unless effective strategy could be employed. Even Tirpitz’s Kriegsmarine (unhindered by naval tradition) found difficulty in devising a focused modern strategy to save the German Navy from total impotence.

For the British Navy of course, strategy was a little more complex. In 1906, Unionist policy dictated that owing to the risk that the ‘German eagle may spread its wings over the sea…we must place Europe virtually under a naval lock and key’. But, by 1909, through the Declaration of London, it was clear to see that close blockade was negated by the technological weaponry of mines, submarines and torpedoes. The Royal Navy therefore fell back on distant blockade, which was hardly acceptable strategy for such monstrous offensive weapons as the Dreadnoughts. Distant blockade would assist the certainly assist the Royal Navy’s task to keep the German High Seas fleet out of the world sea lanes, yet even this remained an excessively cautionary operational war plan. A ‘preventative war’ mentality therefore prevailed and, in bottling up the exits, the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet turned the North Sea into a marine no-mans land. British naval thinking was stuck in a hiatus of its own creation; materially sound yet strategically inept.

Much has been written about Fisher’s lack of applied strategy and how he and his disciples were blinded by the brilliance of technological marvels he had implemented into the Navy. Yet most historians are quick to place this anomaly in its deserved context – that had it not have been for Fisher’s reforms, the Royal Navy would have been hard-pressed to match Tirpitz’s rapidly expanding Kriegsmarine, and Jellicoe may well have been the man who ‘lost the war in one afternoon’. However, almost a century on, this period of naval history with all its misgivings cannot, or at least should not, be laid at the feet of any one individual. Resistance to technological change was surely to have been expected given that proto-technological society was in a materialistic quagmire of its own, fuelled by modern technology whilst still wedded to Victorian methods of Empire building. Fisher may well have constantly refused to establish a War Staff and resented any intrusion into matters of maritime strategy, but the fact also remains that he was far too busy rectifying the materiél shortfalls and the lower-deck humanities to even contemplate the implementation of extensive training.

Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher was responsible for inspiring the Royal Navy to embrace modernity. This task was gargantuan. The changes he implanted were indeed ‘revolutionary’, although some traditions tenaciously resisted this revolution of modernization. British naval officer Stephen King-Hall recalled that there was ‘a number of shockingly bad admirals afloat in 1914’, who were ‘pleasant, bluff old sea-dogs with no scientific training’. Six years of Fisher as First Sea Lord would have made little difference to this ingrained nature of the ‘Nelsonic’ sailor. Although again this was an outright clash between technology and tradition, it was not entirely conservatism that hindered progress, but rather a combination of a lack of new technological strategy, and complacency caused by a century of naval supremacy. Caution ruled naval thinking in 1914, and for this reason the British were not prepared to force battle on the Germans. It was for this reason above all that King-Hall likened the Royal Navy to a ‘prehistoric Brontosaurus’, which had a ‘very big body’ and a ‘very small brain’.